Recently we have seen countless protests and an uproar around the topic of immigration. This seems to not only be in Australia but could be seen happening in many other western countries such as the UK and the United States of America. Whatever the political, social or cultural reasons maybe for these protests, it was clear to me that many people seemed to have developed an assumption that mass immigration and in some cases immigration itself is the cause of disorder in the local economy especially in the housing market. Surging prices have been attributed to the increase in demand for accommodation as a large number of immigrants flooded in during the post-covid period.

When considering the perspective of these assumptions it does make sense as to why one would come to them. There is definitely a correlation between the increase in immigration and the increase in house prices. But does this correlation actually mean there is causation? Let us first confirm the stats around immigration in Melbourne.

Has Mass Immigration Actually Occurred in Melbourne?

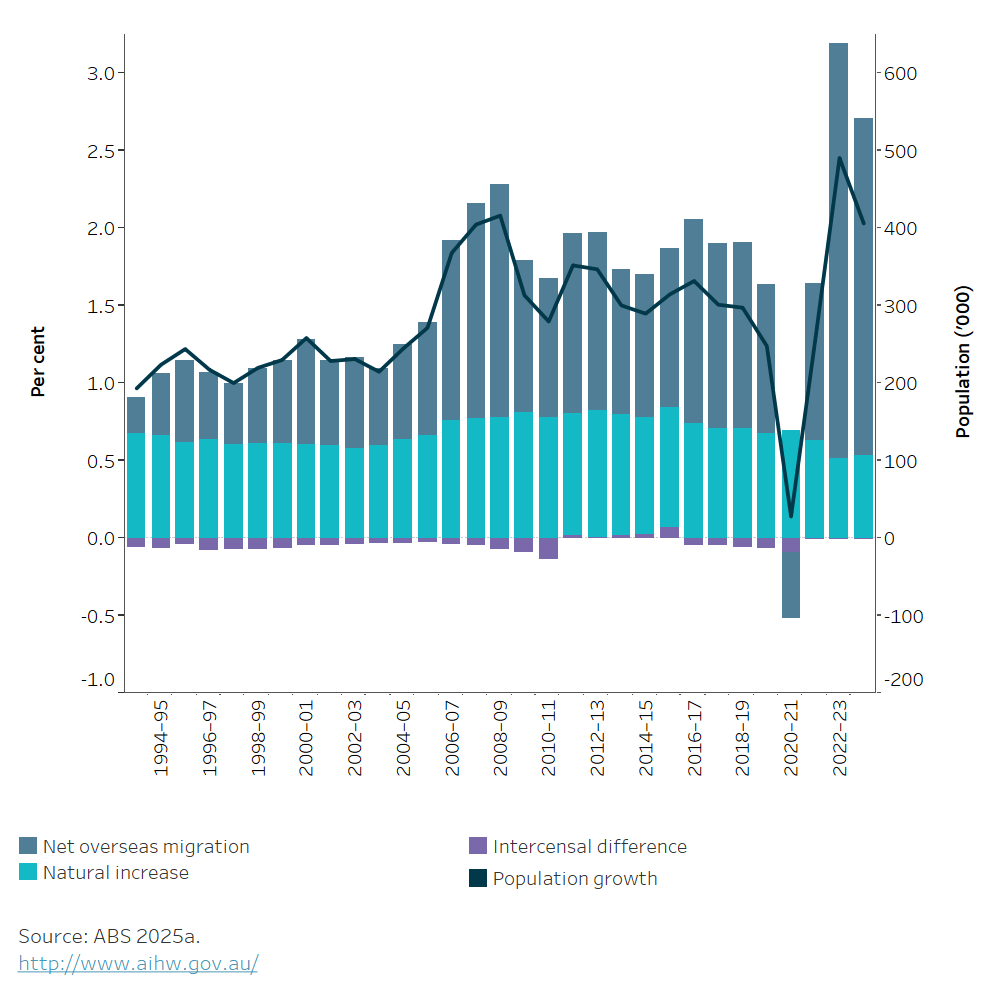

Net Overseas Migration (NOM) has been the primary driver of Australia’s population growth for the past three decades which is the difference between long-term arrivals and departures. With the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic came the first net outflow of migrants that Australia experienced since the second world war. This was a total of 85000 migrants returning home during the years 2020-21. This outflow of migrants was short-lived however as when borders reopened in the year 2022, migrant inflow rebounded at a speed that was not expected in official projections. Figure 1 shows this anomalous behavior of NOM numbers and how rapidly the change occurs within the span of two years.

This means there indeed has been an occurrence of mass immigration during the post-covid period and it has been as dramatic a shift in NOM as has been reflected in the concerns by local population. Furthermore, according to the Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Melbourne had the largest population increase at 142,600 in the period 2023-24.

Is it mass immigration that’s driving the population of Melbourne up?

ABS data for greater Melbourne growth in 2023-24 provides an answer to this question:

- Net Overseas Migration: +121,200 people

- Natural Increase (births minus deaths): +29000 people

- Net Internal Migration: -7600

So it seems that without a doubt the mass immigration post-covid did indeed drive up the population.

Who is Arriving?

Now that we have established that mass immigration actually was a thing post-covid, who exactly is it that’s arriving? Or in other words what type of immigrants are arriving more?

As shown in data by the Department of Parliamentary Services, the permanent migration program does not seem to dominate the surge in NOM. On the contrary, data shows that the largest contribution has come from those on temporary visas. Of this, as stated by ABS, “the largest group of migrant arrivals” has been temporary students with 207,000 people.

Now this particular piece of information is crucial in relation to the housing market. The housing footprint of temporary visa holders, especially students, is quite different to that of permanent residents and citizens.

- Temporary residents, including visitors and working holiday visa holders, are 100% renters and do not participate in the purchase market.

- These migrants cluster geographically, usually closer to universities and inner-city suburbs which have good transport and amenities.

If you know me you may think I am being biased having been both a student visa and temporary working visa holder. But you can easily clear this cloud by looking at the ABS data for the suburb of Carlton, which borders the University of Melbourne, and you will find that it had the largest overseas net migration gain of any suburb in the city at +2900 people.

The true effect of “mass immigration” on Melbourne’s broader housing market therefore seems to be more of a massive, temporary visa-led rental demand shock which has been concentrated in inner-city and university adjacent suburbs.

Drivers of the Housing Crisis

So now that we have an understanding of what all this “mass immigration” uproar was actually about, let’s take a look at how it affects the housing market and if it is directly responsible for the housing crisis.

A Decades-Long Supply Failure

At a glance one would assume the simplest and most reasonable assumption that the housing crisis is caused by an increase in housing demand which exceeds the supply. However, the truth is quite the contrary. Melbourne’s unaffordability is not simply an excess in demand but a structural inelasticity of supply. More people want to work and live where there are better job opportunities such as close to Melbourne CBD. The market however, is unable to respond to this demand by building new homes in these places.

Why exactly is this?

A report by Grattan Institute in 2024 sheds light on this matter. As stated in the report: “the key problem is that state and territory land-use planning systems say ‘no’ to new housing by default, and ‘yes’ only by exception”. The key piece of data from the report is that “87% of all residential land within 30 km of Melbourne’s city center is zoned for housing of three storeys or fewer”. The report shows that Australia’s cities are among the least dense cities that are of their size. This means that there is plenty of room for vertical accommodation, but due to pre-set housing development restrictions, there is a bottleneck in supply.

What this means for the housing market is that when a demand shock occurs, whether that is new migrants, a new generation of locals moving out of their house or a fall in average household size, there is a legal block on the supply of housing which makes it unable to meet this demand. This leaves room for only one variable to adjust. The price.

The foundational driver of housing crisis then? We didn’t guess it right, but it seems to be a policy-driven scarcity.

Finance, Interest Rates and Tax

Supply scarcity certainly seems to be the foundation of the crisis but there are more contributing factors. Another report by the Grattan institute in 2018 states that while increasing migration is certainly driving up demand, housing costs are increasing because “incomes rose, interest rates fell and banks made it easier to take loans”.

How does falling interest rates contribute to this?

- For an interest rate of around 14% for a 30 year mortgage of around $100,000 the monthly repayment would be $1185.

- When the interest rate drops to 7% the same $1185 monthly repayment can now service a loan of $178,000.

This fall in interest rates was orchestrated by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) in order to maintain a low rate of inflation. This change in interest rates doubled the borrowing capacity of households. This new purchasing power was however, not used to build new houses but to bid up the prices of existing houses in the already scarce market.

Is the Major Demand Shock Caused by Immigration Directly Responsible for Rising Prices?

Immigration causing an increase in demand is now undeniable and direct. The growth of new household formation in Melbourne is a good example of how immigration is driving up demand. According to a 2008 senate report from the Australian Parliament, “About half the growth in households in Melbourne is attributable to overseas migration”. The report also noted that, “when you push out the 30-year projection…about 80 percent of the growth is attributable to migration”. This is a clear indication that migration is, and is projected to be, the dominant source of new households in Melbourne.

To further solidify this link, a 2020 study from Monash University analyzed data at the postcode level. I would suggest having a look at this study for a really good analysis of the relationship between immigration and housing prices. The findings of the study were that:

- An immigrant inflow equivalent of 1% of a postcode’s population raised housing prices by approximately 0.9% per year.

- The effects were found to be strongest in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, and specifically in the cities of Melbourne and Adelaide.

We still don’t see how immigration has been directly responsible for the housing crisis?

Citing the same Monash study, the advocacy group in Melbourne, YIMBY reframes their findings by showing that, during the same period, prices increased by 5.95% per year by which they argue that, “At least 80% of house price growth is unrelated to immigration”.

This 80% can be attributed to other factors that we have discussed such as restrictive zoning for construction, falling interest rates and a failure to build to meet demand. So in conclusion:

- Migration (in combination with natural increase) has directly caused population growth.

- And this population growth then causes an increase in demand for housing.

- The restrictive zoning laws cause a constrained and inelastic supply.

This collision between rising demand with constrained supply is what seems to actually be causing the rise in housing prices. This shows therefore that while the migration shock was a contributory cause to the rise in demand for housing, the primary responsibility for the price crisis seems to lie with the long-term, systematic policy failure to allow the housing supply to adapt to any form of population growth.

As summarized in the report by the Grattan institute: “Australian governments are squandering the gains from migration with poor housing and infrastructure policies“. So is the solution to simply “throw out” the immigrants or to reconsider policies around other factors?

Whatever it is, it is always much more nuanced than our emotional outrage tells us it is.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2025). Profile of Australia’s population. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/profile-of-australias-population

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023-24). Overseas Migration. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/overseas-migration/latest-release.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023-24). Regional population. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/latest-release.

- Department of Parliamentary Services. (2010). Migration to Australia since federation: a guide to the statistics. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/migrationpopulation.pdf

- Grattan Institute. (2025). More homes, better cities: Letting more people live where they want. https://grattan.edu.au/report/more-homes-better-cities/

- Parliament of Australia. Chapter 4 – Factors influencing the demand for housing. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Former_Committees/hsaf/report/c04

- YIMBY Melbourne. Can’t we just stop immigration to solve the housing crisis?https://www.yimby.melbourne/faq/cant-we-just-stop-immigration-to-solve-the-housing-crisis

- e61 Institute. (2025). Should housing home money or people?. https://e61.in/should-housing-home-people-or-money/

Leave a comment